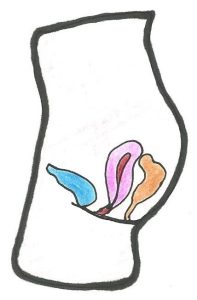

Most women have an anteverted uterus, where the uterus is orientated so that it tilts forwards in the pelvic cavity, lying just behind the bladder.

ANTEVERTED UTERUS

The retroverted uterus is an anatomical variant that is present in 20-30% of women. Sometimes referred to as a tilted uterus, it points to the back rather than the front, often resting on the rectum, and this is considered a normal uterine variant. This is not serious and does not affect fertility nor the ability to conceive.

RETROVERTED UTERUS

Another normal variation is the axial uterus, where the uterus sits upright in the pelvis.

AXIAL UTERUS

A retroverted uterus is often reported following an ultrasound scan or diagnosed after a pelvic examination.

Why does this happen?

A retroverted uterus is either congenital or acquired.

In the first case, the uterus naturally assumes this position during fetal development in the mother’s womb. Therefore, the baby is already born with this anatomical variation.

Rarely, uterine retroversion may also be secondary or acquired, and the uterus is pulled backwards towards the spine by scarring or adhesions. This could be caused by the following:

- Inflammatory processes/infection

- Endometriosis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

- Previous pelvic surgery/adhesions

- Large fibroids

- Menopause

Does having a retroverted uterus cause any symptoms?

The main problem of the retroverted uterus is that it can cause discomfort for some women, such as pain during sex. It also can make a smear test or an ultrasound scan of your pelvis more difficult.

In most cases, the retroverted uterus is asymptomatic. However, the following symptoms may be associated with it:

- Painful bowel movements due to pressure from the uterus on the rectum

- Chronic constipation for the same reason as above

- Pain during sexual intercourse

- More intense menstrual symptoms

- Urinary incontinence or urinary retention depending on the interference of the uterus with the bladder

The retroverted uterus and fertility

A woman’s fertility is not affected just by the orientation of the uterus. However, associated factors that cause a retroverted uterus may have an implication, such as large fibroids or adhesions. Therefore, retroversion could be indirectly connected to infertility.

Another example is endometriosis. In this condition, the tissue lining the inside of the uterus grows outside of it, causing scarring over time. This scar tissue, which can also be caused by surgery or infection, could cause an anteverted uterus to become retroverted. In these cases, the scarring or adhesions, not the uterine lie, may affect the Fallopian tubes thereby preventing the egg and sperm from meeting or implanting inside the uterine wall, leading to infertility.

The retroverted uterus and pregnancy

A retroverted uterus does not increase the chance of miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy, though associated factors such as adhesions and endometriosis do have an implication in an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy.

In women who have a retroverted uterus due to a secondary cause, the uterus often corrects its position during pregnancy because of the weight of the baby as it develops.

Sometimes uterine retroversion occurs during the early stages of pregnancy, but after the first trimester the uterus returns to its normal position because of the growing weight of the baby.

A retroverted uterus can occasionally make it more difficult to empty the bladder in pregnancy. If the growing uterus is tilted very far backwards during pregnancy it could push against the bladder, making it difficult to empty. This can be alleviated by leaning backwards when urinating, which can relieve pressure of the uterus on the bladder. However, it can very rarely lead to urinary retention, which is a medical emergency and should be treated in hospital.

A transient retroversion may also occur in the postpartum stage, due to distension of the pelvic floor ligaments.

How might it affect an ultrasound scan?

Sonographers often report that ultrasound scans are limited due to uterine lie.

Having a retroverted uterus makes it much harder to visualise the pelvic organs with a transabdominal scan, even with a full bladder.

The fundus (top) of the retroverted uterus is much more difficult to see with an abdominal scan because it tilts backwards and is further away from the probe, and usually obscured by the overlying bowel which causes shadowing. Having a full bladder does not help if the uterus is retroverted because it pushes it further away. This can make it particularly difficult to identify an early pregnancy.

A transvaginal scan is preferable for both gynaecological and early pregnancy scanning because the probe is closer to the uterus, whether anteverted or retroverted. It is helpful to have the pelvis raised to enable the probe to be manipulated and therefore view the uterus from every angle.

However, an axial uterus cannot be easily assessed with a transvaginal scan due to its angle of orientation being upright. In this case a transabdominal scan will provide a better image of the uterus.

Later in pregnancy even extending into the second trimester, ultrasound scans can often be more difficult if the uterus is retroverted because the baby sits upright, and accurate measurements are only obtained when the baby is horizontal. Sometimes a transvaginal scan is of benefit.